◡◶▿ SOFT05 | Radical incompatibility

🐄 The thin line between the human filmmaker and the fundamentalist dairy movement. Zero-gravity film sets and toxic junk in the kitchen. | Imaginary Software of the Filmmaking Future Week 05

Missed a week? Joined late? Don’t worry about reading these lessons out of order. Each functions independently. They are sent in a sensible sequence but hardly reliant on it.

Hello, filmmaking students. Hello, curious visitors! And welcome, new subscribers.

It’s week five of our spring term module: Imaginary Software of the Filmmaking Future - How to use, confuse, or avoid your new robot crewmate.

Last week, we covered the differences between different types of automated filmmaking software. Including how:

Motion control filmmakers have programmed themselves a whole new set of problems.

Automatist filmmakers are dreaming of an easy ride.

Generative filmmakers may have got themselves into a sequence they can’t get out of.

The synthetic filmmaker has her hands full with the ‘Everything Pen’ - a movie camera that smooshes together the combined history of everything!

This week, we’ll look at friction. Resistance! From two perspectives:

The necessary friction that an artistic process involves, slowing the process and forcing new forms of exertion;

and the elective resistance posed by Luddites and neo-Luddites in the face of dubious new machinery.

In particular, we’ll cover how:

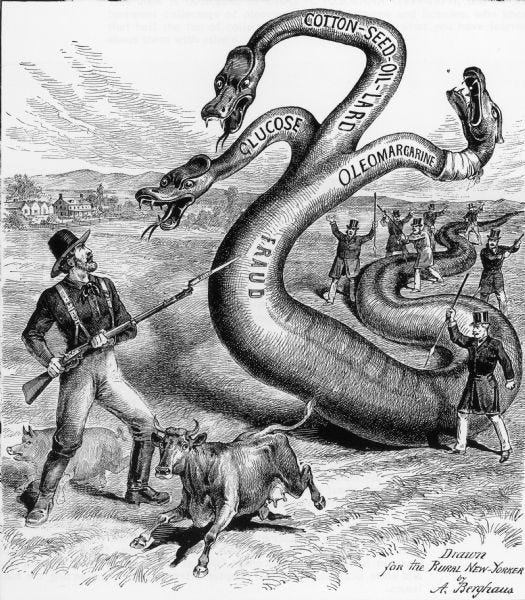

🥞 21st-century resistance to AI art is a lot like 19th-century resistance to margarine.

🔍 Identifying the personal threat or appeal of a piece of filmmaking software may be the first step in conquering it - and your inner demons.

👩🚀 The ideal of ‘zero-gravity filmmaking’ overlooks multiple practical necessities.

🧪 The filmmaker should apply the ‘crunch test’ before emulsioning her picture with toxic junk.

Curiously, I find myself hopping between AI documentation and a thread on home-fermented dairy and making your own kefir cheese while assembling this email. There are probably some parallels and lendable techniques between these pastimes. Today, we will only ‘graze’ the surface of practical AI/fermented dairy analogies.

Margarine

You can hear me deliver this lesson by scrolling up to the header and clicking Listen and/or the play ▸ button.

Dairy loyalists and post-dairy disruptors have been at war since at least the 1870s. In 1869, a Frenchman called Hippolyte Mège-Mouriés invented margarine as a cheap and consistent alternative to butter. An alternative to the complex process of making butter. And to the variable qualities produced by small dairy farmers. The dairy lobby was furious.

Both groups have continued to make disparaging claims about the other’s choice of spread over the decades. Claims about flavour. Claims about health properties. Claims about the unwholesome source of the ingredients.

But margarine was just the start. Non-dairy alternatives have boomed in the 21st century. This boom has prompted the dairy lobby to campaign for tighter definitions around disputed categories. Categories such as “milk.”

Milk is the lacteal secretion of one or more mammals, they said. Milk is what is milked from hooved animals. It is literally “milk,” can’t you see?

Today, people say the same thing about human art.

Promise/threat

New software is designed and marketed on a set of promises. Often, one particular promise will catch your attention, and perhaps draw you in. Identifying the appeal of the promise may reveal an issue you didn’t realise had been troubling you. Hello!

New software may promise to be:

Easy

Cheap

Scaleable

Powerful

New

Lucrative

Innovative

Fun

Necessary, or

To save you from working in close proximity to other people.

Note which promise triggers a gut response. You needn’t reject the software - or a solution it offers - just because your gut response is immense gratitude or fear or hunger. Maybe this software is just the solution you need! But first, examine the problem that the telltale solution has flagged.

Do you really want a third-party magic spell to do away with the issue that’s haunting you? Or might you code your new awareness of that problem into your own internal software? Make it the star of your movie?

Meanwhile, the design and marketing of some softwares position them less as a set of promises than threats. Does the software threaten you? That’s useful, too! Slow down. What are you afraid of? Hello! Goodbye!

Friction

Even the messiest, most joyfully intuitive filmmaker has dreamed of a perfect system. A recipe! A fluid recipe for making movies without doubt or contingency. Low-friction, zero-gravity filmmaking.

To find a system for filmmaking that runs like water: you turn on a tap, and out flows gorgeous cinema, in measured 80-minute gushes or sold by the gallon and divisible at any point. Pleasurable in quantity. And you can turn it off when you’re full, or you run out of money or friends.

On reflection, many would stop short before turning on that tap.

Friction shapes a creative work in time and space. Every mode of expression has its modes of friction. Every stroke is friction.

Friction includes the rub of your soles against the pavement as you trudge from shop to shop asking for leftover cardboard. Or the balls of the boom operator’s shoulders grinding in their sockets. But friction is also attempts to negotiate with or inspire your collaborators. And, of course, there is mental (or imaginative) friction and the inner frictions of electronic hardware.

The traditional live-action film production involves:

physical,

social, and

neuro/electrical

resistance. This resistance is critical to the outcome of a particular movie. Different friction = different movie.

Friction slows you down. Friction forces you to navigate. But friction also provides a sense of the landscape. Where would you be without friction?

Low-friction filmmaking

Many a filmmaker has sought to minimise friction↑ in their process. Sensibly so.

They’ve tried to lubricate the filmmaking machine with money. Or to smooth out the design. Or to use low-friction tools and techniques; powerful, easy-play hardware and software.

Computer software is a popular choice for the reduction of friction in the filmmaking process. Computer work displaces shoulder joint friction to the fingertip skin, which usually grows back. It certainly saves on shoe leather. And desktop computer work can reduce or transform lots of other types of friction.1

Software is not friction-free. But it is often lower-friction than the processes that it replaces or complements. Often, this reduction in friction becomes the whole point of using the software. Oh no! Better if the filmmaker chooses software with a creatively appropriate type of friction. And not just an amenable level of friction.

Bolder filmmakers have faced up to friction head-on. Cheek-to-cheek, as it were. Bolder filmmakers have acknowledged that friction is a necessary and even desirable force. These bolder filmmakers can be split into two broad and foolhardy groups:

The endurance filmmaker believes that friction is a test of a movie’s strength. Or the strength of its underlying idea - which likely holds strong, stubborn even, in the filmmaker’s mind.

The endurance filmmaker may even assume a linear connection between the difficulty of making a film and the quality of its outcome. !

The intrepid filmmaker believes that friction is the stuff of filmmaking. And that discovering and testing high-friction areas can be both fruitful and pleasurable.

This filmmaker also believes in recipes: she sees that to make something more easy - by providing instructions to follow - also makes it more difficult - by providing instructions to follow.

At various points between these poles, you’ll find a filmmaker who believes a bit (or a whole lot) of both. Werner Herzog! Werner Herzog is one of those.

Beyond the poles, you’ll find cowards and geniuses. Slooping around in the grease of low-friction filmmaking. Who knows what their film will turn out like. Who knows where they’ll end up!

Toxic junk

Filmmaking is the synthetic art. Filmmaking always involves and thrives upon the putting together of things. Things from disparate sources. Smooshing them together and resolving them into a cohesive flow.

But synthetic filmmaking software involves the smooshing of unidentifiable junk. Obscure and uneven training data. Forgotten burger ads and Victorian edutainment - perhaps. You never know quite what's in it; and now it’s in your movie.

The best chefs wouldn't make a meal this way. The best painters wouldn't use pigments like this. (Unless that was their point. To make beauty and redemption or condemnation out of unidentifiable waste.)

However, the filmmaker is not a chef. Cinema is a suggestive art of moving surfaces. It is physically, if not spiritually, shallow. And so it is common for a filmmaker to have little beyond a surface idea of the provenance of her audiovisual matter. Try as she might, she can’t know everything. She can’t even know much!

And so, the filmmaker modulates and juxtaposes her mystery materials. Modulates and juxtaposes them to create meaning and suggestion. And not to provide an exhaustive technical guide to the movie’s underlying components.2

How much should a movie acknowledge its filmmaker’s ignorance of:

the history of a location,

an actor’s bio-chemical source material,

the reasoning behind the cadence of an unscripted dog bark, or

even a vague idea of the source of a colour, shape, rhythm, gesture or assumption coughed up by her synthetic filmmaking software?

(Through the use of:

explicit acknowledgment,

sly audiovisual gossip,

raw production techniques,

a radically open production process,

(the inclusion of barely compatible, flamboyantly diverse ‘found’ or collaborative elements), or

incompetent cover-up efforts?)

Not every film needs to flag its filmness. Nor interrogate its underlying socio-political and material genealogy to the last pixel. To insist on this would probably usher in a painful era of global neorealism.3

But there is a difference between the unidentifiable toxicity of the junk in her synthetic filmmaking software versus that of the filmmaker’s leading man or her hired wind machine. The difference is in the crunch.

The output of the synthetic filmmaking software is smooshed beyond recognition. There’s no telltale crunch when you get a lumpy bit of forgotten burger ad or Victorian edutainment. Because there are no lumps, ergo, no crunch.4

And so, if the filmmaker chooses to work with pre-smooshed toxic junk, what techniques might she develop to give it its crunch back? Is there software that can do that? Who developed it, and why?

Please share your thoughts, queries, and exercises from this week’s lesson in the comments.

Once upon a singularity in Hollywood

Mike Gioia notes a curiously counterintuitive form of resistance we might expect as generative AI makes it into the mainstream cinema: the big bucks filmmakers may focus on more difficult areas of AI filmmaking to differentiate themselves from the average basement hobbyist.

“Hollywood won’t have the appetite for other categories of weirder AI filmmaking, especially if it’s the same process a YouTuber in Minnesota can do,” writes Mr Gioia. “The incumbent film industry will crave higher barrier-to-entry areas.” (This is from Mr Gioia’s Armchair Taxonomy of AI Filmmaking, a useful companion to last week’s UPV guide to automatic filmmaking methods.)

Hollywood may even invent deliberately complicated ways to use this “easy-use” software just to flex their muscles at the adoring masses! Those crazy bastards might propel us into the cinematic singularity just because they can! (And they are just as insecure as the rest of us.)

In next week’s newsletter: naive robots swarming your production’s breakfast buffet.

Don’t forget the footnotes ⬇️ 👀.

Class dismissed!

~Graeme Cole.

(Principal)

📹 Unfound Peoples Videotechnic | Cloud-based filmmaking thought. ☁️

🐦 Twitter | ⏰ TikTok | 📸 Instagram | 😐 Facebook | 🎞️ Letterboxd | 🌐 Website

Snack consumption changes qualitatively, although the quantity of snacks consumed may rise, depending on the duration of the work and proximity to the bakery.

Which, in any case, would be impossible since a movie’s fundamental ingredients are nearer mush and goo than nuts and bolts.

(Although we might expect resistance from fringe groups of ‘transparent’ filmmakers who acknowledge their materials without recourse to neorealism: the constructivists, the clunkyists, the brutalists, and the plastic and coltan phantasists, for example.)

Even the sweatless, thermoplastic filmmaking of the late-era live-action Hollywood movie has areas of higher or lower crunch. The glossy film depends on a certain level of crunch to maintain human interest. A real stunt here. A charismatic performance there. There’s no true charisma without crunch.

You had me at biochemical source material.