◡◶▿ AMAT12 | Love

❤️🩹 Maya Deren, George Kuchar & Dziga Vertov walk into a bar, eyes spinning like propellers. Plus: Wolf Rilla's useless sex manual. | Advanced Amateury Week 12

About us: “Unfound Peoples Videotechnic (UPV) is a roaming absurdist film and video academy. Our Substack mailing list is a pipeline for esoteric filmmaking knowledge and technique. And it is the school’s primary means of mass communication.”

Hello, hello! Please settle down. Sit well and make yourself comfortable.

In last week’s lesson, we learned how:

The “amateur professional” approaches her amateur filmmaking practice with the rigour of a pro.

The “professional amateur” works professionally as a filmmaker but imbues her practice with amateur technique and non-technique.

These concepts are threaded through with an unstable physics of personal energy, snacks, funds, viability, will, purpose, luck, inertia, and doubt.

There was also an exercise. Did you do the exercise?

This is the final class in our Advanced Amateury module. Week 12 of 12. Oh!

Addendum: upcoming topics include cinematography, set design, sound, and the future of filmmaking.

Today, we’ll discuss:

🐶 How the amateur might recalibrate Dziga Vertov’s “mechanical eye.”

🤟 Why the amateur is not a negative imprint of the professional, but an original agent of compulsion and spirit.

💰 What Maya Deren’s weird beef with weird burglars teaches us about love.

🖍️ The toddler technique that defies mediaphysics.

Missed a week? Joined late? Don’t worry about reading these lessons out of order. Each functions independently. They are sent in a sensible sequence but hardly reliant on it.

Let’s start.

A loving dog

You can hear me deliver this lesson by scrolling up to the header and clicking Listen and/or the play ▸ button.

“I’m an eye,” wrote Dziga Vertov, wrongly. “A mechanical eye. I, the machine, show you a world the way only I can see it. I free myself for today and forever from human immobility.

“I'm in constant movement [!]. I approach and pull away from objects. I creep under them. I move alongside a running horse’s mouth. I fall and rise with the falling and rising bodies.”

Vertov’s discipline and his energy are to be saluted. But consider the following:

“I’m a dog,” the filmmaker might suppose. “A loving dog. I, the animal, show you a world the way only I can see it. I free myself for today and forever from human immobility.

“I’m in constant movement. I approach and pull away from objects. I creep under them. I move alongside a running horse's mouth. I fall and rise with the falling and rising bodies.”

Choosing love

Imagine for a moment that we accept that the amateur is defined by what they are not. Imagine we believe an amateur is an amateur because they are not:

trained or

professional or

profitable, for instance.

A common reaction is to explain these “nots” as symptoms of laziness, neglect, or failure:

“The amateur has not bothered to get training.”

“She hasn’t succeeded in finding work or selling tickets to see her film.”

These are the assumptions your dole officer or disinterested uncle might make.

But might her unprofessionalism be a wilful choice? Mightn’t she be afforded the same respect as Big Mr Trained Filmmaker Man?

“A boy of twelve, with a twin brother, a movie camera, and a dream: To turn his brick-infested borough into a paradise of exotic 300-pound birds living in temples of dark and imposing majesty, honeycombed with cubicles of the most exquisite Puerto Rican pink, and all of them interlaced with an awesome network of clogged plumbing.” - George Kuchar

Here are some reasons she might have chosen to be amateur:

To disrupt ingrained ways of doing things.

To communicate in new ways or unfashionable old ways.

To maximise joy and minimise stress.

To allow for possibilities that professionalism excludes.

To revel in the mess (of humanity; of play; of production).

Lower economic risk.

There are ways to achieve these ends without choosing to be an amateur. But since these ends de-prioritise acclaim and career and profit, it is necessary for another force to take their place. For the amateur, that force is love. To be an amateur is to choose from a certain pool of means to these (or other) ends. (A love pool.) To be an amateur is to choose to prioritise love. (It may not be your choice at all).

If this sounds romantic, try to remember that love is not always nice.

Carefree

A bold word or phrase indicates that an instruction of the same name and concept appears elsewhere in this module.

To be carefree is to eschew any and all discipline. Anything goes! Could that work?

The imperfectionist is not carefree. The imperfectionist cares intensely about creating the right imperfection. Imperfectionism is a kind of guiding rule or moving target. In short: discipline.

And look at the two-year-old with her crayons. She has two serious modes of appraisal:

Aesthetic. She draws and adjusts until she is satisfied. There is no pay-off quite like the click when a toddler adds a stroke that she finds aesthetically correct.

This toddler is not carefree even if her aesthetic values are obscure to you.

Symbolic. She is satisfied that a mark she has made can ‘stand for’ something in her picture (or in the broader activity of which the picture is just a part).

This toddler is not carefree; she prioritises. “Perfect is the enemy of getting to the next part of my process,” she might say.

Priorities, standards, and discipline facilitate freedom. Freedom without discipline is chaos.

But could that work?

“[M]aking a movie is like conducting a love affair which can easily go wrong. No textbook can teach a lover to love, and the most sophisticated theory of sex technique is worse than useless if it lacks the fundamental emotion for which it is only a channel of expression.

“Amateur, in its most literal sense, means ‘lover of’—and no good film is ever made without love. On the other hand, amateurs wrongly distrust a kind of inbred discipline which characterises the professional approach.” - Wolf Rilla

Well. Maya Deren offers us a muddy case study. Deren criticised the “pseudo-Zenists” of the Beat era for their lack of discipline. Their improvisations made her think “of nothing so much as an amateur burglar in a strange apartment, turning all the drawers onto the floor, cutting up the mattresses, ripping off the backs of pictures, and in general making one un-godly, clumsy mess in a frantic search for a single significant note.”

Instead, the serious artist, Deren wrote, should be the “skilled bank robber” of their own “vast and hidden reserves of past experience and skill.”

Deren had a point to illustrate. And fierce convictions against “aggressive noodling” to reinforce. (For herself as much as her readers.) But there is a little crack here. A glimmer. The word “amateur.”

“Amateur” was not a word Deren used lightly. “The very classification “amateur” has an apologetic ring,” she once wrote. “But that very word - from the Latin “amateur” - “lover” means one who does something for the love of the thing rather than for economic reasons or necessity. And this is the meaning from which the amateur filmmaker should take his clue.”

So we must return to this image of the “amateur burglar.” One who loves the process:

risking entry to a mysterious flat,

tossing clothes and furniture with gleeful abandon,

savouring the rip of the polyester mattress skin as it yields to the craft knife.

Don’t you think there is a breed of amateur burglar who forgets all about the “significant” gem they sought? Who finds, instead, spontaneous joy for the process, the feeling of destruction, carefree, giggling all the while? Who fills their swag bag to a pleasing roundness with stuffing from torn scatter cushions?

It is love without care. Love as sensation, not contemplation. And despite Deren’s dismissal of this style of burglary, her use of the word “amateur” suggests a certain envy for this burglar’s giddy sense of freedom. A mode of living and loving that may have as much to do with disposition as deliberate technique.

Right. Okay.

But is it possible to be carefree and still achieve results you can accept?

But isn’t love - in the realm beyond filmmaking and crayoning and burglary - splattered with that which we cannot accept?

Could that work?

Oh no!

Oh no! It’s that toddler again with her crayons. Have you seen her draw a picture of her best friend running?

It starts with a line. The line is the route. The speed of the crayon on the paper represents (perhaps at scale) the speed of the runner. The drawing is live. An animation, really, in real-time, but which leaves a full trace of every frame behind it. Wait! There are no frames. It is liquid motion. It is impossible to tell if the friend’s two feet are ever off the ground at the same time (particularly since the crayon never leaves the page).

So: a diagram or data visualisation rather than a picture. But not just a representation - a channeling. A divination. The friend is in her wrist, in her crayon, in the line, in the movement of the line, and all over the paper, while she draws. When the drawing (verb) ends, what you see is just the shell. (The drawing [noun] is never finished. Where do you think the friend goes next?)

Where did she hear of such a format?! Let’s hope she never loses it!

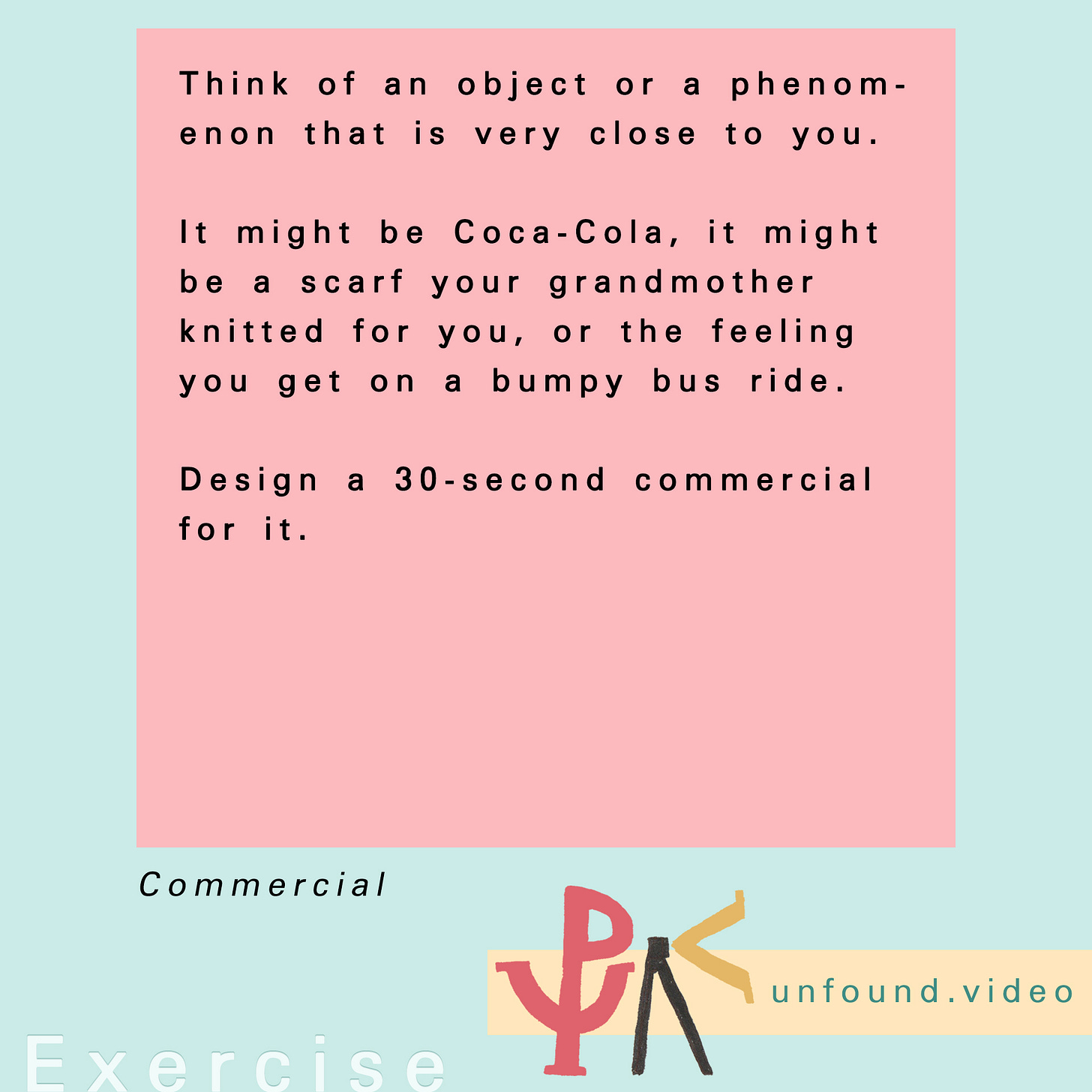

Exercise: Advert

Please share your thoughts, queries, and exercises from this week’s lesson in the comments.

Love me. Love, Me.

That’s the end of Advanced Amateury. Let’s return to the subject of amateury later! In the meantime, if this series has been of any help to you, please spread the love by

forwarding this email,

posting the URL of any of the lessons to your personal website or media outlet,

misquoting the program at length in the classroom, bathroom, or bar.

It really helps!

If you have feedback or requests, please leave a comment or reply to this email. It’s ok.

Let’s take a short break from learning. Next week we’ll make a little recap of the module you’ve just completed. And I’ll reveal what this newsletter will be up to - in your inbox, of all places - over the summer.

Smoke if you got’em.

~Graeme Cole.

(Principal)

🦋 Bluesky | 🐦 Twitter | 📸 Instagram | 😐 Facebook | 🎞️ Letterboxd | ⏰ TikTok |🌐 unfound.video